Scientists have begun to harness DNA’s powerful molecular machinery to build artificial structures at the nanoscale using the natural ability of pairs of DNA molecules to assemble into complex structures. Such “DNA origami,” first developed at the California Institute of Technology, could provide a means of assembling complex nanostructures such as semiconductor devices, sensors and drug delivery systems, from the bottom up.

While most researchers in the field are working to demonstrate what’s possible, scientists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) are seeking to determine what’s practical.

According to NIST researcher Alex Liddle, it’s a lot like building with LEGOs—some patterns enable the blocks to fit together snugly and stick together strongly and some don’t.

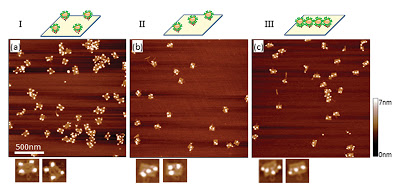

DNA origami: NIST researchers made three DNA origami templates designed so that quantum dots would arrange themselves: (a in the corners, b) diagonally (three dots), and (c in a line (four dots). The researchers found that putting the quantum dots closer together caused them to interfere with one another, leading to higher error rates and lower bonding strength.

Credit: Ko/NIST

“If the technology is actually going to be useful, you have to figure out how well it works,” says Liddle. “We have determined what a number of the critical factors are for the specific case of assembling nanostructures using a DNA-origami template and have shown how proper design of the desired nanostructures is essential to achieving good yield, moving, we hope, the technology a step forward.”

In DNA origami, researchers lay down a long thread of DNA and attach “staples” comprised of complementary strands that bind to make the DNA fold up into various shapes, including rectangles, squares and triangles. The shapes serve as a template onto which nanoscale objects such as nanoparticles and quantum dots can be attached using strings of linker molecules.

The NIST researchers measured how quickly nanoscale structures can be assembled using this technique, how precise the assembly process is, how closely they can be spaced, and the strength of the bonds between the nanoparticles and the DNA origami template.

What they found is that a simple structure, four quantum dots at the corners of a 70-nanometer by 100-nanometer origami rectangle, takes up to 24 hours to self-assemble with an error rate of about 5 percent.

Other patterns that placed three and four dots in a line through the middle of the origami template were increasingly error prone. Sheathing the dots in biomaterials, a necessity for attaching them to the template, increases their effective diameter. A wider effective diameter (about 20 nanometers) limits how closely the dots can be positioned and also increases their tendency to interfere with one another during self-assembly, leading to higher error rates and lower bonding strength. This trend was especially pronounced for the four-dot patterns.

“Overall, we think that this process is good for building structures for biological applications like sensors and drug delivery, but it might be a bit of a stretch when applied to semiconductor device manufacturing—the distances can’t be made small enough and the error rate is just too high,” says Liddle.

Molecularly directed self-assembly has the potential to become a nanomanufacturing technology if the critical factors governing the kinetics and yield of defect-free self-assembled structures can be understood and controlled. The kinetics of streptavidin-functionalized quantum dots binding to biontinylated DNA origami are quantitatively evaluated and to what extent the reaction rate and binding efficiency are controlled by the valency of the binding location, the biotin linker length, and the organization, and spacing of the binding locations on the DNA is shown. Yield improvement is systematically determined as a function of the valency of the binding locations and as a function of the quantum dot spacing. In addition, the kinetic studies show that the binding rate increases with increasing linker length, but that the yield saturates at the same level for long incubation times. The forward and backward reaction rate coefficients are determined using a nonlinear least squares fit to the measured binding kinetics, providing considerable physical insight into the factors governing this type of self-assembly process. It is found that the value of the dissociation constant, Kd, for the DNA–nanoparticle complex considered here is up to seven orders of magnitude larger than that of the native biotin–streptavidin complex. This difference is attributed to the combined effect that the much larger size of the DNA origami and the quantum dot have on the translational and rotational diffusion constants.

26 pages of supporting material

If you liked this article, please give it a quick review on ycombinator or StumbleUpon. Thanks

Brian Wang is a Futurist Thought Leader and a popular Science blogger with 1 million readers per month. His blog Nextbigfuture.com is ranked #1 Science News Blog. It covers many disruptive technology and trends including Space, Robotics, Artificial Intelligence, Medicine, Anti-aging Biotechnology, and Nanotechnology.

Known for identifying cutting edge technologies, he is currently a Co-Founder of a startup and fundraiser for high potential early-stage companies. He is the Head of Research for Allocations for deep technology investments and an Angel Investor at Space Angels.

A frequent speaker at corporations, he has been a TEDx speaker, a Singularity University speaker and guest at numerous interviews for radio and podcasts. He is open to public speaking and advising engagements.