The Brookings Institute published the English translation of “Collapse of an Empire: Lessons for Modern Russia,” which was a bestseller in Russia. Written by Yegor Gaidar, an economist who was Russia’s acting prime minister between 1991 and 1994, the book uses information from Soviet archives to tell the story of the last few years of the Soviet Union. It tries to shoot down the “myth” held by most Russians that the Soviet Union was “a dynamically developing world superpower until usurpers initiated disastrous reforms.” It also warns that Russia should avoid the peril of another collapse in oil prices.

What happened, states Mr. Gaidar, is that Soviet grain production stagnated between 1966 and 1990. Meanwhile, 80 million people moved from farms to cities. New Soviet output of oil and gas was not sufficiently expanded to provide the hard currency needed to buy grain abroad. Eventually, the Soviets had to borrow foreign money to buy grain.

The result was that Moscow could not suppress revolt in its empire – as it had done in earlier years in East Germany, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia – without losing Western loans.

Gaidar argues that if the Soviet military had crushed Solidarity Party demonstrations in Warsaw, “the Soviet Union would not have received the desperately needed $100 billion from the West.” Similarly, when the Soviets tried to use force to reestablish control in the Baltic states in January 1991, the reaction from the West, including the United States, was: “You can choose any solution, but please forget about the $100 billion credit.” The Soviets backed down.

Oversimplifying history, Gorbachev was perceived as weak for allowing the dissolution of the Russian empire, overthrown in a military coup, and eventually replaced by Boris Yeltsin.

Gaidar’s thesis isn’t accepted in its entirety by other experts. Leon Aron, a fellow at the AEI and a friend of Gaidar, says glasnost – Gorbachev’s effort to bring openness and transparency into the activities of Soviet institutions, with greater freedom of information – opened the USSR to new political, ideological, and spiritual ideas. “The economic side made collapse faster,” he says.

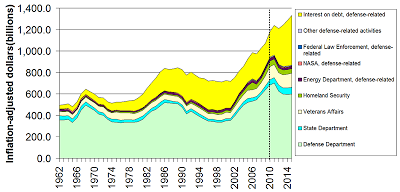

Goldman figures that Gorbachev’s dismantling of the Soviet military-industrial complex was the main cause of the collapse. The aluminum industry, for example, supplied raw material for military aircraft, the steel industry for the 60,000 tanks facing the West. Afterwards, “there was no longer anything there,” he says. At its peak, the military absorbed 30 percent of total Soviet output. Today, Russia spends about 5 percent on its military.

Free Copies of the Book

Brian Wang is a Futurist Thought Leader and a popular Science blogger with 1 million readers per month. His blog Nextbigfuture.com is ranked #1 Science News Blog. It covers many disruptive technology and trends including Space, Robotics, Artificial Intelligence, Medicine, Anti-aging Biotechnology, and Nanotechnology.

Known for identifying cutting edge technologies, he is currently a Co-Founder of a startup and fundraiser for high potential early-stage companies. He is the Head of Research for Allocations for deep technology investments and an Angel Investor at Space Angels.

A frequent speaker at corporations, he has been a TEDx speaker, a Singularity University speaker and guest at numerous interviews for radio and podcasts. He is open to public speaking and advising engagements.